People base their decisions on subjective memory—how they feel about a memory—more than on its accuracy, researchers report.

When we recall a memory, we retrieve specific details about it: where, when, with whom. But we often also experience a vivid feeling of remembering the event, sometimes almost reliving it. Memory researchers call these processes objective and subjective memory, respectively.

The new study shows that objective and subjective memory can function independently and involve different parts of the brain.

“The study distinguishes between how well we remember and how well we think we remember, and shows that decision making depends primarily on the subjective evaluation of memory evidence,” says coauthor Simona Ghetti, professor at the psychology department and the Center for Mind and Brain at the University of California, Davis.

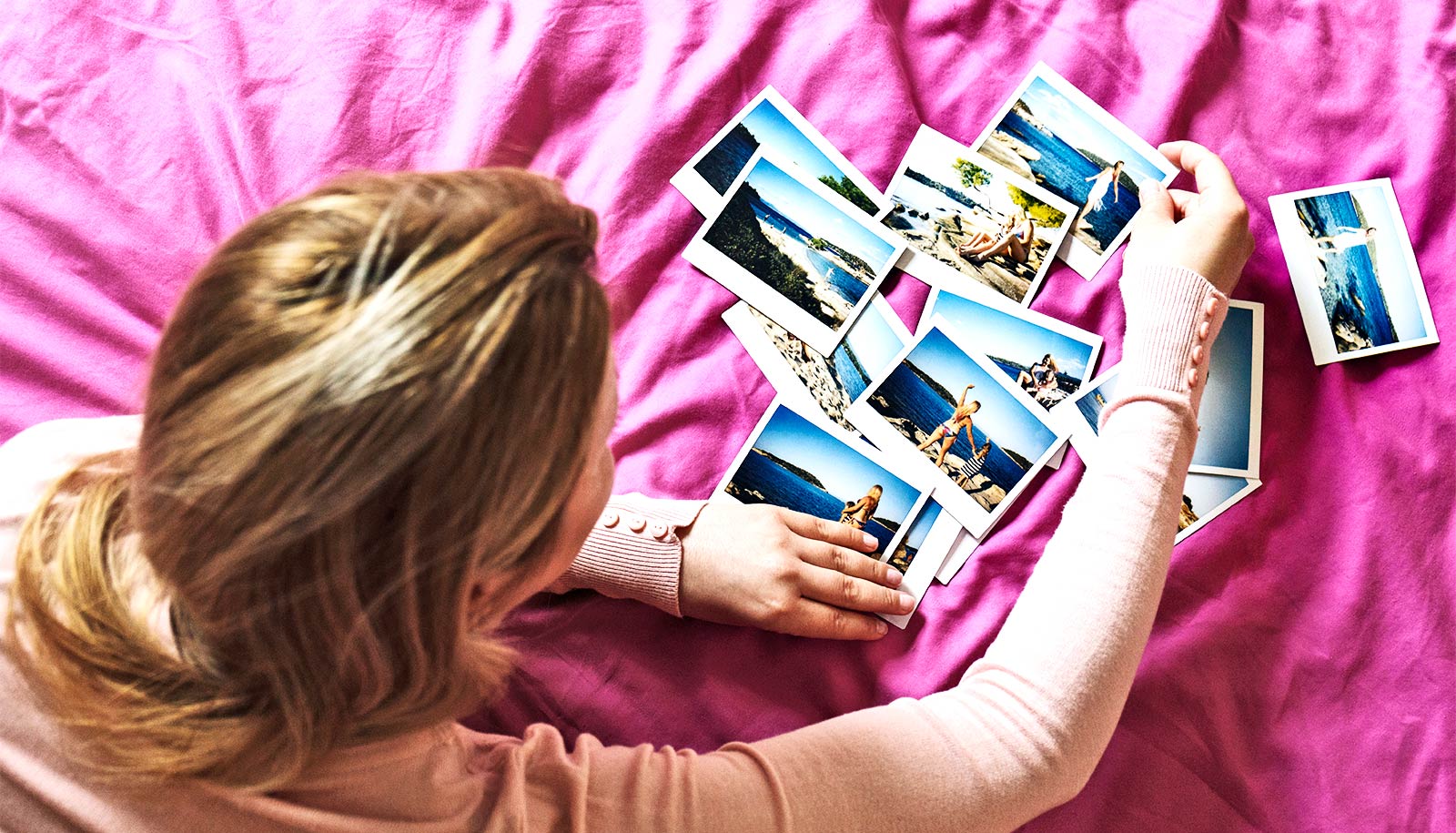

The researchers tested objective and subjective memory. After showing volunteers a series of images of common objects, the researchers showed them pairs of images and asked them to determine which of the two they had seen before.

The researchers asked the volunteers to rate the memory as “recollected,” if they experienced it as vivid and detailed, or as “familiar” if they felt that the memory lacked detail. In some of the tests, image pairs included a target image and a similar image of the same object. In others, the target was shown with an unrelated image from the same original set. For example, a chair might be shown with another chair shown from a different angle, or with an apple.

This experimental design allowed the researchers to score objective memory by how well the volunteers recalled previously seeing an image, and subjective memory by how they rated their own memory as vividly recollected or merely familiar. Finally, participants were asked to select which images to keep or discard, assigning them to a treasure chest or trash bin.

The team also used functional MRI to measure brain activity during this task.

The results showed higher levels of objective memory when participants were tested with pairs of similar images. But, people were more likely to claim that they remembered vividly when looking at pairs of dissimilar images.

Participants were more likely to base their decision about whether to keep or trash an image on how they felt about a memory rather than its objective accuracy.

To give a real-world example, a person could have a vivid memory of going to an event with friends. Some of the actual details of that memory might be a bit off, but they may feel it is a vivid memory, so they might decide to go out with the same people again (after the pandemic).

On the other hand, if someone has learned to use similar power tools doing odd jobs around the house, their memories about those objects may be quite specific.

“But you might still feel that you are not recalling vividly because you might question whether you are remembering the right procedure about the right tool. So, you may end up asking for help instead of relying on your memory,” Ghetti says.

The fMRI data showed that objective and subjective memory recruited distinct cortical regions in the parietal and prefrontal regions. The regions involved in subjective experiences were also involved in decision making, bolstering the connection between the two processes.

“By understanding how our brains give rise to vivid subjective memories and memory decisions, we are moving a step closer to understanding how we learn to evaluate memory evidence in order to make effective decisions in the future,” says postdoctoral researcher Yana Fandakova, now an investigator at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin.

The work appears in the journal eLife. The James S. McDonnell Foundation supported the work.

Source: UC Davis